“Sigillum Civitatis Novi Eboraci”

— this Latin phrase translates to Seal of the City of New York

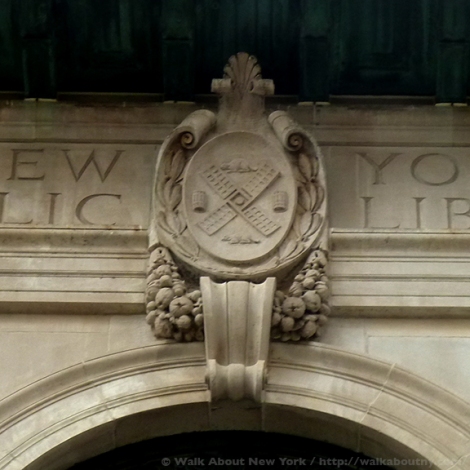

From school houses to library buildings to police shields, the Seal of the City of New York is displayed throughout the Big Apple. Made up of some easily recognizable symbols, as well as some obscure ones, and often displaying different dates, the Seal can be elaborate or simple and rendered in a variety of materials. The Seal is an excellent way to learn the fundamentals of the city’s rich and complex history. Estimates are that, first created by the Dutch, then by the English, and then by New Yorkers, the Seal has been changed at least eight times. Let’s explore this corporate representation of the Big Apple.

By 1915 more than two centuries had passed where loose standards were applied, allowing builders and sculptors to take artistic license with the Seal on buildings and monuments throughout the city. In that year the Common Council ordered that history books be consulted, and the Seal was standardized, but not completely. Not until 1977 was the date fixed officially at 1625, marking the founding of the Dutch trading post, Nieuw Amsterdam.

A shield at the Seal’s center displays two beaver and two flour barrels in the spaces between a windmill’s sails. This is the most basic part of the Seal, and most often it is used without the other elements. Prized for their pelts that were used for fur, and their skins that were made into felt for hats, beavers were the foundation for Nieuw Amsterdam’s economic success under the Dutch. How important was the beaver to the early economy? A ship known as the Arms of Amsterdam brought news of Peter Minuit’s purchase of the island in 1626 to the Kingdom of the Netherlands; but it carried a more valuable cargo: 7,246 beaver skins, 675 otter skins, 48 mink skins, 36 lynx skins, and 34 Muskrat skin. Beaver skins were so valuable in the province of Nieuw Netherland they were used as currency. John Jacob Astor (1763–1848), one of the wealthiest 19th-century New Yorker, made his fortune from the beaver trade; he then invested that fortune in New York real estate, where he made another fortune.

Beginning in 1664 the Dutch trading post changed hands; the British ruled until they lost the War for American Independence. A decade later the number of beavers trapped for their skins and pelts had dramatically decreased. The loss of revenue because of this could have proved devastating, if not for the actions of Sir Edward Andros. Appointed governor-general for the joint colonies of New York and New Jersey in 1674, Governor Andros first decreed that all goods destined for export from the Province of New York must pass through the port of New York. Thereby raising New York’s profile and importance.

Next Governor Andros granted a monopoly to New York City in 1680. Wheat from the Province of New York could be ground into flour, packaged and shipped to markets in North America, Europe, and as exotic a place as the Caribbean, only in New York City. Flour quickly became the lifeblood—the new ‘beaver’—of New York.

Arduous and multi-staged the process of separating wheat into flour and bran was called bolting. The new law, the Bolting Act took its name from the process itself. Governor Andros’ decree did for New York what the Erie Canal would do for it 125 years later: boosting the economy and putting New York at the center of regional, national, and international commerce. Because of bolting the cooper’s trade—barrel-making—became a booming business. As a result, the flour barrel earned its prized place on the Seal.

Picturing the sails of a windmill on the Seal is acknowledgment of three important parts of New York City’s history. Although associated with the Dutch in popular culture, when the sails of a windmill first appeared on the Seal the city was under English rule. Reason number one was that windmills were used to grind wheat to flour. The second two reasons involve the city’s Dutch heritage. Many Dutch families, some in positions of authority, had windmills on their coats-of-arms. The windmill’s arms mimic the saltire, or St. Andrew’s Cross, and three saltires, arranged vertically, are central to the coat-of-arms of the city of Amsterdam, New York having been Nieuw Amsterdam.

The Seal’s most prominent features are the figures of a sailor and a Native American; they first were used in 1686, one year after James, Duke of York, for whom the city was renamed, succeed to the throne as James II, King of the United Kingdom. To illustrate that the province of New York had been patented to him by his brother, Charles II, James’ ducal coronet was added in the crest position to the Seal by 1669. James was the proprietor of the province.

Façade of the Jefferson Market Library, once the Third-Judicial District Courthouse, Greenwich Village.

Facing out from the Seal itself, a sailor occupies the dexter, Latin for “right,” position. The sailor, because of the Latin name for his position, is named Dexter. He holds a lead plummet, used for measuring water depths, in his right hand. Some mistakenly say he is holding a plumb, a carpenter’s tool. Including the sailor recognizes the importance that shipping played in the economic development of New York. From 1830 until the 1950s New York was the busiest port in the world.

The Native American, holding a bow in his left hand, is a Lenni Lenape man, a member of the Algonquin tribe, that first lived on the island of Mannahatta, meaning “land of many hills” later Anglicized to Manhattan; he represents the human origins of New York City. Standing in what is called the sinister position, “sinister” is Latin for “left,” the Native American should be holding up the shield, along with the sailor. One serves as the “dexter support,” the other as the “sinister support.” The figures should not be leaning on the shield. Both figures stand on a laurel branch, as a symbol of peace between the native population and the newly-arrived settlers.

Following the American War for Independence a bald eagle replaced the ducal coronet in the position of a seal called the “crest.” Facing and rising towards a sailor the eagle stands on a hemisphere where the coronet once was.

Bearing the Latin words, SIGILLUM CIVITATIS NOVI EBORACI, (Seal of the City of New York) a ribbon takes up the lower two-thirds of the Seal. “Eboraci” is the Latin name for the city of York in England; it translates as ‘Place at the Water.’

Used for determining latitude a navigational tool called cross-staff, one of the more obscure items on the Seal, can be seen pointing skyward over the right shoulder of the sailor. Emphasizing the importance of the shipping industry to New York’s prosperity, this is the symbol that has been often omitted from the Seal.

Used as a symbol of victory a laurel wreath encircles the entire seal; crowns of laurel leaves were awarded to victors in the Ancient Greek Olympic games. The City Clerk is the custodian of the City Seal.

Our Downtown Manhattan Tour includes much about the city’s Dutch roots. Plan now to book this Tour when it returns to the schedule in the spring. Take the Tour; Know More!

ALL PHOTOS AND TEXT, EXCEPT CREDITED QUOTES, © THE AUTHOR 2020

Thank You for explaining the Cross-Staff.

Yours being the first article I’ve found to do so

LikeLike